Above: Jessica Colotl unwittingly became an activist for the undocumented student movement after she was arrested for a minor traffic violation in 2010, and immediately placed into deportation proceedings.

A Patchwork of Policy

Editor's Note

The lives of undocumented people in the United States are at the whim of state officials who create policy to fill the gaps in federal legislation.

Some undocumented students in the United States are admitted to college with resident tuition and state aid. Others - different only in where they live - are banned from public institutions.

Reporter Natalie Delgadillo, opinion columnist Ryan Nelson and photojournalist Angie Wang spent 11 months piecing together what it means to be an undocumented student in the United States. They looked at the lives of students in California, where policies are comparatively lenient, and in Georgia, where students are subject to some of the harshest higher education policies in the country. They found that the stories of students in both states shed light on the arbitrary nature of immigration policy in a country where federal action on the issue continues to stall.

The Bridget O’Brien Scholarship Foundation has funded eight years of UCLA student journalism with global reach and local impact, including this project. To learn more about the scholarship, visit rememberingbridget.com.

*Note: Name has been changed to protect student privacy.

"My family came here in pieces."

Valerie* sits at a table on the Kerckhoff patio, folding and refolding the napkin she had just used for lunch. When she is not moving her hands, she holds them carefully, flat on the tabletop and very still. She is calm but guarded, seeming to carefully consider her words.

“My dad came first,” she said. “My brother and I came a year or two later. My mom two weeks after that.”

Valerie is a fifth-year student at UCLA. She and her family migrated to the United States from Mexico when she was 3 years old, and they have lived in California for more than 20 years. All of her family members are undocumented, which means they do not have legal authorization from the federal government to live in the United States.

“Growing up, from the time I can remember, I always knew I was undocumented,” she said. “And I’m a little bit cynical about my future at this point.”

California tells one very specific story about undocumented student access to higher education. But so much of the story can be found elsewhere, in states like Alabama, Georgia and Arizona.

Valerie is one of the 5 to 10 percent of undocumented students with a high school diploma struggling to earn a college degree in the United States. She is one of dozens of students interviewed for this story, and one of thousands across the country engaged in a similar fight.

But while federal action on the issue of undocumented immigration continues to stall, the experiences of those thousands of students are largely dictated by disparate state policy. Depending on the state they’ve landed in, undocumented students can be barred from public institutions, or they can be admitted with resident tuition rates and state aid.

California tells one very specific story about undocumented student access to higher education. But so much of the story can be found elsewhere, in states like Alabama, Georgia and Arizona. Undocumented students living in these states are prevented by state or university policy from receiving in-state tuition, or they are banned from attending public institutions.

Students in Georgia are subjected to some of the nation’s most draconian regulations, which include a university policy banning them from attending the state’s top schools. During the last five years, undocumented students in this state have begun advocating for themselves, finding new ways to fight against policies that make it almost impossible for them to get a higher education.

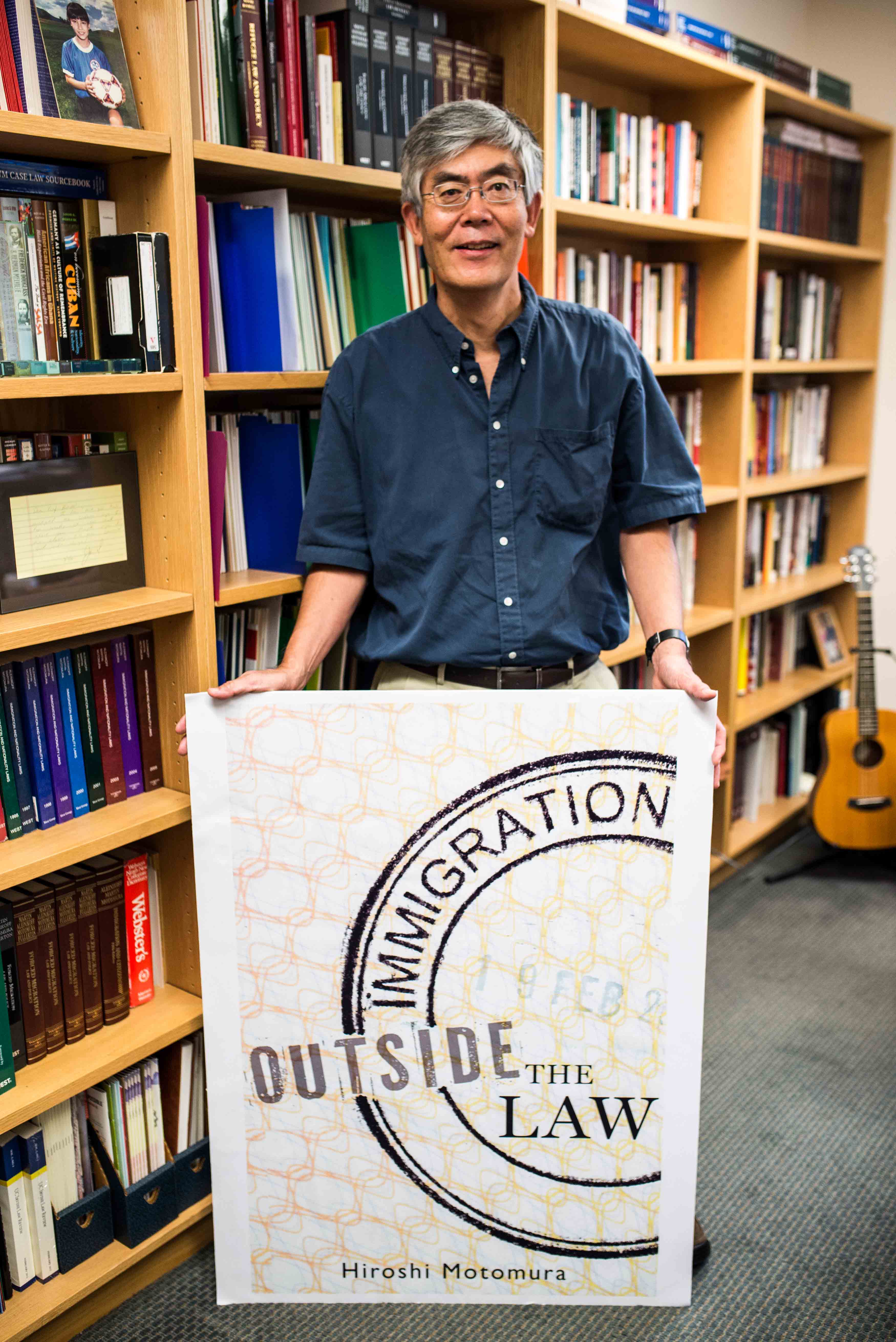

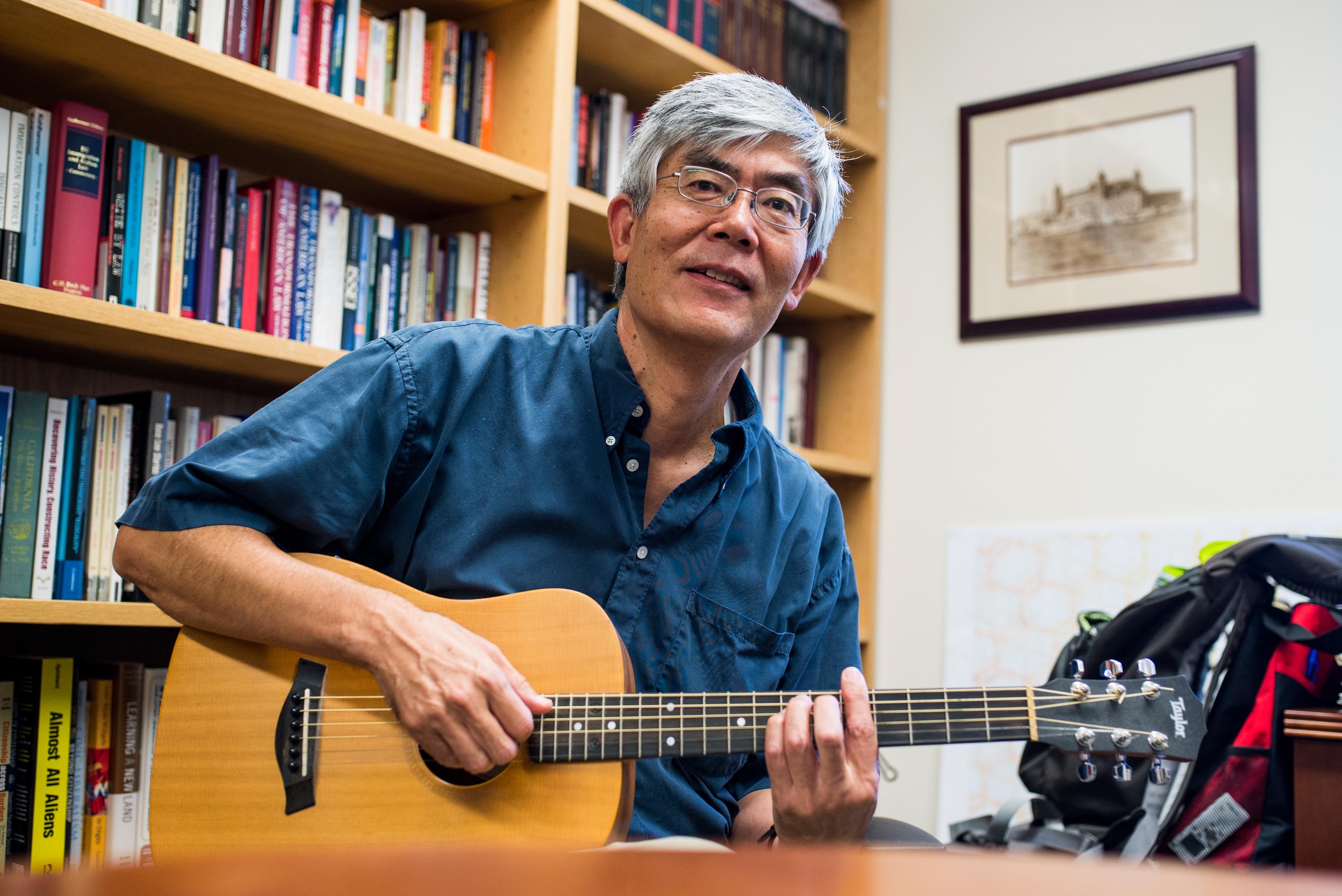

Hiroshi Motomura

UCLA law professor talks policy reform for undocumented immigrants

After volunteering as a consultant on deportation cases, UCLA law professor Hiroshi Motomura decided to focus his teachings on immigration policy. Click to expand.

In California, like everywhere in the U.S., undocumented people live under the threat of deportation and have trouble accessing basic resources. At the University of California, criticism from undocumented students has been particularly acute since former Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano was appointed president of the UC system.

Healthcare access for undocumented individuals by state

* Percentages collected from sample populations of undocumented individuals in each state. Samples for some states were not large enough to make accurate calculations.

Data from the National Immigration Law Center and Migration Policy Institute.

Many undocumented students and immigrant rights activists took her appointment almost as a personal rebuke, saying her single biggest accomplishment at the Department of Homeland Security was deporting more than 400,000 undocumented immigrants during every year of her tenure. In her government position, Napolitano took the lead for the Obama administration in an aggressive immigration enforcement effort, making her the architect of a policy that deported more immigrants than any previous president – Republican or Democrat.

Even so, this state remains one of the nation’s most hospitable for undocumented people, inside and outside the realm of higher education. Undocumented residents can obtain valid California driver’s licenses, undocumented children have access to state-funded health care and some undocumented students, like Valerie, have access to in-state tuition rates and state aid for college.

Georgia and California exist on opposite ends of a huge spectrum of policy. Their stories shed light not only on one another, but on every state and every undocumented resident who must navigate a sea of policies that lie somewhere in between.

State policy – Georgia

Jessica Colotl was a fourth-year political science student at Kennesaw State University in Cobb County, Georgia, when she was pulled over in a campus parking lot for “impeding the flow of traffic.”

She was driving around her Georgia campus like she would have on any other Monday morning looking for a parking space. Colotl was waiting behind a car she thought was getting ready to back out of a spot when she saw lights flashing behind her.

“I thought the policeman was just going to tell me, ‘Hey, you can’t be doing that.’” Colotl said. “Obviously, that’s not what happened.”

Colotl was driving without a license. She had no Social Security Number and thus no way of obtaining one. She had no form of identification on her except her school ID.

So instead of a simple traffic ticket, Colotl was arrested, sent to Cobb County jail and put immediately into deportation proceedings.

Undocumented individuals by the numbers

Click for an interactive breakdown of the undocumented population by the numbers

It was 2010 – before the Obama administration’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program protected people like Colotl, who came to the United States as children and have spent most of their lives here.

She was also living in a state that has historically passed among the strictest anti-immigration legislation in the country. And she was going to school in Cobb County, one of the first counties in the country to adopt a far-reaching program meant to allow state and local officers to participate in immigration enforcement measures.

Under the program, which has since been discontinued by the federal government, a traffic violation like driving without a license could become a deportable offense.

After Colotl’s arrest, she was moved from the Cobb County jail to an immigration detention center in Alabama, where she begged, unsuccessfully, to be allowed out on bond so she could finish her last year of school. She was detained for more than a month before a judge ordered her to leave the country at her own expense.

Facing imminent deportation, Colotl’s optimism and strength began to unravel.

“When you’re in that situation, in detention for that long, you just start to lose hope,” she said.

Even while her situation seemed to be a lost cause, her KSU Lambda Theta Alpha sorority sisters rallied – if Colotl was going to have to leave the country, they believed, people should know what happened to her. They organized a march at the Georgia Capitol and drew media attention to Colotl’s case that she believes swayed government officials to take another look at her case.

She had given up hope when a guard approached her one day in May and told her she was going home.

She was confused, not understanding whether he meant her home in Georgia or in Mexico.

”Georgia,” he said.

Jessica Colotl

Former student to use law school to help other undocumented individuals

Jessica Colotl found herself at the forefront of undocumented student activism in Georgia, after being arrested for a minor traffic violation in 2010. Click to expand.

She didn’t know it at the time, but she had – rather suddenly – been granted one year of deferred action by the Department of Homeland Security. She was sent back to Georgia and given time to finish school before she would have to either re-apply for deferred action or leave the country.

“I was so happy that I was going to get to finish school,” she said. “I was okay with leaving the country if I had to, so long as I could get my degree.”

Before she would have had to re-apply for deferred action a second time, Colotl got another reprieve. President Barack Obama announced DACA, and she qualified for the program. She has been able to remain and work in the country.

Her story has what she called a “kind of” happy ending. She got to stay. But the attention her case drew to undocumented students in Georgia was not all positive.

Colotl was paying in-state tuition at KSU. When that information became a part of the public narrative of her case, Colotl unwittingly became a symbol of deep injustice for Georgians who saw illegal immigration as a threat to the state’s economic resources. No undocumented person, they reasoned, should get a subsidized education on the Georgia taxpayer’s dime.

“I was so happy that I was going to get to finish school,” she said. “I was okay with leaving the country if I had to, so long as I could get my degree.” Jessica Colotl

Anti-immigrant rumblings were growing louder among some state legislators, said Charles Kuck, a prominent Atlanta immigration lawyer who represented Colotl and later hired her as a paralegal at his firm.

“There was talk about a bill in the legislature that would take the university system’s sovereignty away in order to ban undocumented students from public schools,” Kuck said.

The University System of Georgia, wary of that level of government oversight, headed the politicians off. The same year that Colotl was arrested and granted deferred action, it introduced its own policies to restrict undocumented students’ access to schools.

Policy on undocumented students: CA vs. GA

Data from the California Student Aid Commission and University System of Georgia.

One of the new codes specified that undocumented students could not qualify as state residents, meaning that they would no longer be able to pay in-state tuition. That more than doubled the amount they would have to pay for school, practically overnight.

University system officials also directly banned undocumented students from attending the five most competitive and prestigious public universities in the state. Because those universities routinely reject Georgia citizens, the university argued, it would no longer admit students who were in the state illegally.

The system’s new codes have made Georgia one of the most hostile states for undocumented students. Many of the state’s undocumented students have tried to turn to private institutions, often out of state. Even if they get in, the huge expense of living away from home and paying private-school tuition often precludes this option. Most attend only if the school can offer them financial aid that doesn’t rely on federal money, for which they cannot qualify.

Most of the undocumented Georgia residents interviewed for this story have not yet managed to find a way to go to college, in state or otherwise.

Jessica Colotl is lucky in some ways – she spent more than a month detained in an Alabama immigration detention center, but she also got her degree. As a paralegal at Kuck Immigration Partners, she works steadily toward her goal of becoming an immigration lawyer, gaining experience at one of the most prominent firms in Georgia.

She has her own office, tucked at the end of a long hallway. It’s organized and immaculate, a fall-scented candle sitting on her desk, filling the whole hallway with perfume.

Next: Colotl and Valerie’s very different lives speak to the arbitrary nature of enforcement in a country where federal action on immigration continues to stall. Undocumented immigrants are neither uniformly condemned nor universally protected in the United States – nobody agrees on what to do. As long as that continues to be true, state lines will continue to be a powerful predictor of the direction of undocumented people’s lives.